I came to Room 103, an elementary school classroom, for the first hour of the day, every day for the first few months of school. I watched as the teacher, Ms. K, gradually showed the children how to be students. I was interested in her thought-process and decision-making.

I came to Room 103, an elementary school classroom, for the first hour of the day, every day for the first few months of school. I watched as the teacher, Ms. K, gradually showed the children how to be students. I was interested in her thought-process and decision-making.

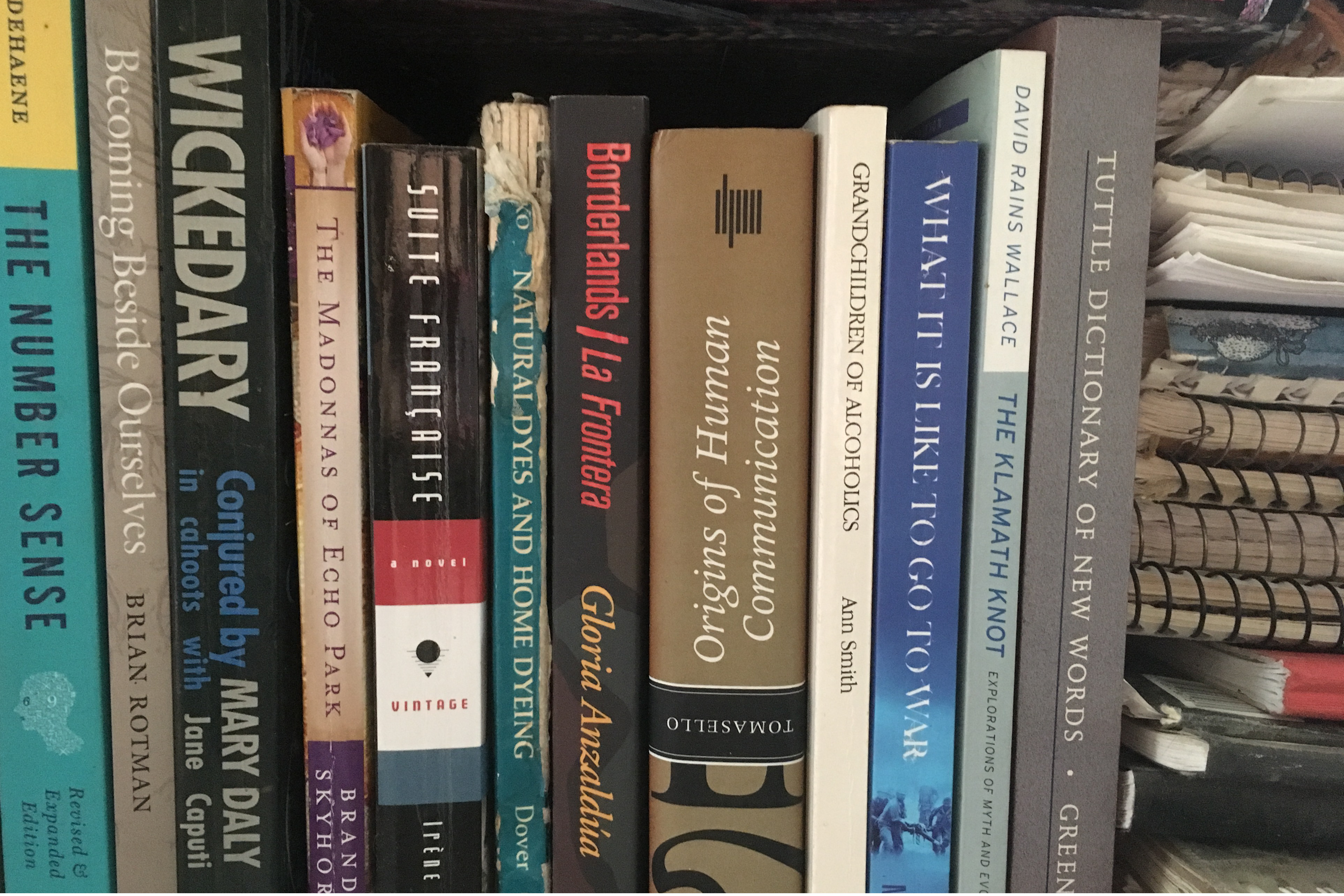

I would arrive in the morning before the students and settle into a spot in the corner where I could see the whole room. I had drawn a map of the classroom which included a seating chart and various special areas, such as the Library and the Science Table. I took notes on a stack of photocopies of that map by sweeping the classroom and writing down key words to describe what was happening in each area. Every five minutes, I would turn the page over and start on new blank map. I ended up with a sloppy shorthand record of who did what and when and where during the time that I was there.

After leaving Room 103 I would go immediately to the silence of my car, review the pages, expand and clarify the notes, trying to get down everything that I remembered. I also added to a collection of notes that I was keeping about what I thought I understood. I made lists of questions.

After a week or so, one of the students finally pointed to me during the discussion time and asked, “Who is she?” Ms. K explained that I was learning about being a teacher by noticing everything that happened in the classroom. I let students look at my notes. The children were delighted when they deciphered a record of something they remembered, but for the most part the notes were pretty inscrutable to them and they lost interest.

After that, in the morning before the classroom day officially began, one of the children would often take me aside to show me what was new in the room. It could be something that belonged to the whole classroom, such as a new display of Reading Words or set of objects in the Math Area. Sometimes a student would want me to record something about them individually. They might take me over to see how they were putting an art project into the “completed” basket, perhaps, or wave a note from home at me and demonstrate how they were now about to deliver it to Ms. K.

From the very first day, Ms. K had been projecting the notion that interesting and exciting things happen in the classroom all day long. She never told the students they should talk to me about what they found important. When the children came to me on their own to point things out, their enthusiasm was genuine and I could often sense how they were proud of their surroundings and their accomplishments.

“Sometimes I am jealous of you!” Ms. K told me. “I wish there was a way for me to do the same thing. Just sit and watch what is going on. It is so important to see it all. You have to learn everything you can about them. They aren’t going to just tell you. How can they possibly know what I need to understand about them, much less put it into words?”

“I’m the one who has to keep it all moving along,” she continued. “So I have to watch for what’s important to know at the same time I’m making decisions about what to do and say. Observation. That’s what these education students should be doing more of. They worry so hard about what they will do when they teach a single lesson, when what they really need to learn to do is observe. It’s hard to observe when you are weighted with the responsibility of being the teacher. I wish they could get more practice now.”

This is part of a sequence of essays about visits to Room 103. Names and other identifying details have been altered to protect people’s privacy.