Throughout my teaching career, I alternated between periods of teaching and periods of learning about teaching. That’s how I found myself in Room 103, an elementary school classroom, observing. Each day, for the first hour of the day, for the first months of the school year, I parked myself in a corner and took notes.

Throughout my teaching career, I alternated between periods of teaching and periods of learning about teaching. That’s how I found myself in Room 103, an elementary school classroom, observing. Each day, for the first hour of the day, for the first months of the school year, I parked myself in a corner and took notes.

It was the teacher, Ms. K,* who suggested that I come at that time of day. “It’s the block where I have ‘Critical Thinking/Problem Solving’ in my lesson plan,” she said.

She told me that her colleagues shuddered at the thought of someone sitting in their classroom every day, watching. There was an assumption that in the name of “helping,” the observer would mostly be finding fault. Many schools seemed afflicted with revolving doors through which so-called experts came and went, naming problems and offering “constructive” criticism. Was I really going to to simply observe and ask questions?

“I want something substantial, now,” declared Ms. K. “Not just, ‘Your slip was showing this morning.’”

Even though she seemed to feel less vulnerable than other teachers, Ms. K still expected me to be “critical” and tell her what she was doing wrong. Yet as the weeks progressed, I felt less and less able to do that. She did everything so well, so much better than I could have. The closest I could come to making “suggestions” was to second-guess a few details.

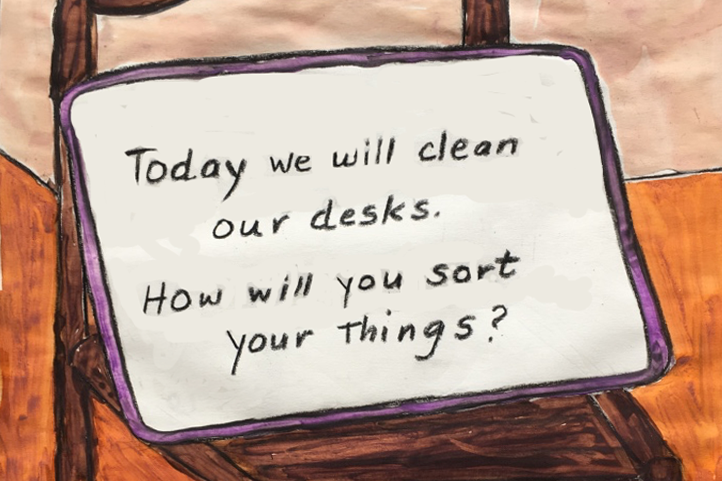

Much of the “critical-thinking” and “problem-solving” in those early weeks of school had to do with working on the complex puzzle of how to function in the classroom. How do 25 children and one adult live and work together for the bulk of the day, in one room, five days a week? What do you do with yourself? When do you talk, read, listen, write, walk around? Why are we doing what we are doing? What is the best thing for you?

Watching Ms. K show her students how to navigate these questions was like watching someone weave a tapestry from a bucket of tangled fishing line. She projected these assumptions overtly into the room and taught the students about them:

- School is serious, though we are active and jolly, even silly sometimes. The purpose of school is to learn, to grow, and to develop what’s wonderful about ourselves. That’s serious.

- The people who work in this room are, without exception, interesting human beings with unique perceptions, feelings and potential. To spend every day with them, to learn from them and understand them is a gift.

- Everything is interesting and exciting—objects, ideas, people. Nothing exists in the world as a dull lump. It can always be reflected upon, connected to other objects or ideas, and shared with other people. Our minds do this naturally. This can be both exciting and overwhelming.

- Everything and everyone deserves to be regarded and treated with kindness and respect—the dead bugs on the Science Table, each other, our work.

- The highest standards for ourselves operate at all times. We deserve no less.

In this sequence of essays, I will describe how, during those first nine weeks of school, Ms. K taught 25 children how to be the students of Room 103.

*Names and some identifying details have been altered to safeguard people’s privacy.