We sat at his feet in the living room and he quizzed us. Who made you? God made me. Why did God make you? God made me to know, love, and serve him in this world.

We sat at his feet in the living room and he quizzed us. Who made you? God made me. Why did God make you? God made me to know, love, and serve him in this world.

Our dad. He was God’s stand-in, the head of our house.

After the catechism, we moved to arithmetic. Then he read the newspaper. On Tuesdays he watched Combat! and on Wednesdays, The Gallant Men.

Like everyone’s dad, our dad fought in The War. The dads fought in The War, came home, married moms, and now they go to work.

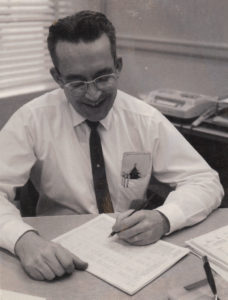

Our dad had glasses and blue eyes, smoked Taryton cigarettes, and wrote with his left hand. Every Sunday on the way home from Mass, he pulled into the Sunoco station and said Fill ‘er up! to the attendant whose blue coveralls read, Larry in red stitches above his pocket. I thought Sunoco was Catholic gas.

Perhaps we could have been a family that was a lot richer, but our dad never, ever, did anything that was greedy or dishonest.

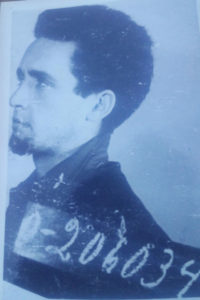

He didn’t shoot anyone in The War. He was a navigator. It wasn’t until after we grew up and moved away that he got a POW license plate holder. Mom rolled her eyes. Not that he ever talked about it. He said there was nothing to say.

We knew that a guy jumped out of the plane ahead of him and his parachute didn’t open. Did that make you scared to jump? If you didn’t jump, they pushed you.

Did you try to escape? No.

Somebody got killed once. A guy who went outside during an air raid. We understood that he should have known better. Tell us about the time the guy got killed. I already told you. Tell us about the stew with worms. We were glad to get it.

I watched Citizen Kane with him once, and it helped me understand how deeply he believed that if you were diligent, respectful of authority and of your elders, things would always be okay.

always be okay.

Towards the end of his life, some of the fellas he flew with and who were imprisoned together tracked each other down. They were all in their 80s so there was no question of a reunion. But I suppose that getting in touch made them remember more clearly who they were then.

Our dad was drop-dead handsome in his uniform, a movie star, perfectly pressed, stretched asleep in a photo with his head in the crook of his arm on the couch. Our grandmother took that picture because she said all he ever did after he came home from The War was sleep.

I remember the way he sneered down to the yellow roots of his nicotine-stained teeth and hissed that Saddam Hussein was a Hitler.

The last time I visited him we sat at the kitchen table. He was on the phone with the Social Security Administration, straining with his hard-of-hearing to navigate its automated system. He just wanted to tell someone why he was calling, and they were asking for zip codes and dates of birth. He mumbled his answers. I’m sorry I do not recognize your response, would you like to return to the main menu? He shouted and told them how stupid they were, which of course brought more recorded nonsense. He swore and got angrier, finally yelling that they could go figure out for themselves that Mom was dead.

And I sat there let him do it, didn’t try to help him or stop him. Because he’d just never been the kind of person who’d put down his head down on the table and cry.