One of the more absurd things I’ve done in Haiti is teach Spanish. Not that it’s absurd for Haitians to learn Spanish. They share an island with the Spanish-speakers of the Dominican Republic. Due to Haiti’s extreme poverty, young people consider slipping into the underground work force in the DR, living there as second class citizens, and facing situations where even the least bit of Spanish might be an advantage.

One of the more absurd things I’ve done in Haiti is teach Spanish. Not that it’s absurd for Haitians to learn Spanish. They share an island with the Spanish-speakers of the Dominican Republic. Due to Haiti’s extreme poverty, young people consider slipping into the underground work force in the DR, living there as second class citizens, and facing situations where even the least bit of Spanish might be an advantage.

Haiti has strong ties with Cuba. Cuban doctors staff many clinics and hospitals. Cuban aid workers have long been first responders to Haitian disasters. Haitians want to be able to converse with these visitors and possibly make connections to help with education and careers. There is nothing inherently absurd about teaching Spanish in Haiti.

The absurd part of my teaching Spanish is that I barely speak it. The first foreign language I learned was French. A new mental process called “foreign language” awoke in my mind. When my thoughts slipped through it, they came out in French. Later, I took a few few Spanish classes and found the two languages to be very similar. Most of their vocabulary comes from the same Latin roots, and a lot of their tricks of grammar are identical. If I ran my thoughts into the foreign language space and through a prism called “Spanish,” rudimentary Spanish would come out.

It was on that basis, during a visit a school in rural Haiti, in some conversation I half understood, a conversation which took place in Haitian Creole, I must have told somebody I spoke Spanish.

Haitian Creole is the language I had gone to that place to learn. This language borrows a sizeable portion of its vocabulary from French and then strings the words together in ways that are definitely not French. Knowing French is both a help and a hindrance in learning Creole. You can guess a lot of vocabulary and make yourself understood even when your Creole is garbled with French, because any Haitian who has been to school has learned a little bit of French. If they understand you, they probably won’t correct you. Talking funny is part of your foreignness. If you already know French and you want to learn Creole, you have to suppress your French vocabulary so you learn words by listening to the people around you.

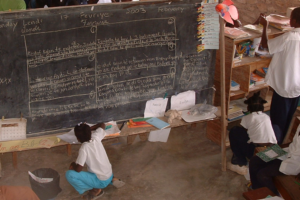

I had come to this place to “volunteer” at a school for a few months. Never having worked in a Haitian school, and not yet speaking the language, I was hesitant to say that I had any particular thing to offer. I didn’t want the mantle of some know-it-all from across the beyond and shirked it by insisting, “I’ll do whatever you want.”

Which is how I found myself teaching Spanish.

Was I teaching Spanish? There were no materials, so the class was conversational. I prepared lessons about asking directions, meeting new people, or the things you could find in the market, but the topics the students wanted to talk about on any given day took us far afield pretty quickly. My so-called spontaneous Spanish always worked on delay. I could almost feel ratchets turning and trap doors clacking as I tried to burble it up from where it was forgotten underneath the French I was trying to hold back. Before any actual words could pass my lips, they had to be checked to ensure they were words from the Spanish I was trying to remember, and not the Creole I was trying to learn or the French I was trying to forget. Sometimes I would hear the things that came through that blender and out of my mouth and cringe at the idea of an actual Spanish speaker passing by the classroom.

It’s peculiar to be from a wealthy place and go to these poor places, these underdeveloped nations and third-world countries. You hope to do something good, not make the usual mess. Instead of imposing yourself, you are going to do what they want.

Do whatever they want. That’s not the foundation of a relationship of equals.

You still have to do something together in order to get acquainted, though. Whatever they want is probably as good a thing to do as any. Then, as you try to do whatever they want, the interesting questions stops being, “What do they want me to do?” The interesting question becomes, “Who are they?”